Tyrone and Huntingdon to renew century-old rivalry

Ask most football fans about their biggest rivals and it often boils down to a couple of factors.

Location is one. Teams that reside near each other tend to want to beat one another – Bellwood-Antis and Tyrone are a prime example in Blair County. Hollidaysburg and Altoona are another.

Shared success is another. Teams that win want to beat the best, and when two teams that win at a high level play in the same conference or district, there’s bound to be elevated levels of animosity.

Bad blood sometimes comes into play, and that’s when rivalries really become heated.

For Tyrone and Huntingdon, in the earliest days of a series that dates back to the Roaring Twenties, it was all of those things and more. Much more.

Add to the list vandalism, assault, and spite.

For Tyrone and Huntingdon, in the earliest days of a series that dates back to the Roaring Twenties, it was all of those things and more. Much more.

Add to the list vandalism, assault, and spite.

It was a series that boiled so hot that eventually it was called off in the 1940s, and even then the cancelation was a stick-it-to-em maneuvering more than a move to reestablish sportsmanship or protect the health of the players.

To put it bluntly, the programs hated each other, from the highest levels of their school districts to the water boys on the sidelines.

The brief respite in the 40s and into the 50s allowed the bad blood to cool, but the rivalry never went away.

That’s one aspect of the series that makes this week’s District 6 3A playoff game special. Tyrone will travel to Huntingdon’s War Veterans Field Friday for the team’s fifth playoff confrontation, renewing the series for the 96th time and the second time this season.

Tyrone and Huntingdon have played more than twenty-two hundred games combined in their rich histories. They were the dominant forces in the Big 8 conference in the 80s, 90s, and early 2000s. The Bearcats have more than 700 wins and six District 6 titles. Tyrone is at 690 victories and has won Districts 10 times.

And after all of that, it still comes down to the battle of who’s-the-best between the long-time rivals, who first squared off in 1922.

SEEDS OF RIVALRY

Football in the borough was in its infancy then, in only its second season, while the Bearcats were a little more seasoned, having started their program in 1901.

In that way, the team’s first pairing wasn’t as much a competitive game as it was a lesson. Huntingdon won 45-0, and the final score made the game look more competitive than it actually was. But Tyrone was young, and its upstarts began to figure things out in 1923. It took a late touchdown for the Standing Stone Boys to edge the Orange and Black 13-9, and when the teams met in 1924, Tyrone was finally ready to break through with a win.

The Golden Eagles had the goods in 1924. Wilbur “Wib” Ammerman was the star, leading the state with 30 touchdowns, while Merl “Tarzan” Stonebreaker was a future college All-American and just as wild as his nickname suggested. When the teams played at the Athletic Park in East Tyrone in November, it was a battle, one that was intensified in the week leading up to the game when Huntingdon Superintendent E. R. Barclay accused Tyrone of employing homer referees for the game.

But it didn’t take an impartial judge to spot play that went over the line in this one. With Tyrone up 7-0 in the fourth quarter, a Huntingdon player jumped with two feet on the chest of Ammerman while he was on the ground, and a brawl nearly ensued. But Ammerman stayed in the game to score the game-sealing touchdown and Tyrone went on to its first unbeaten season.

Little instances like that go a long way in establishing narratives for Tyrone and their fans it was that Huntingdon was a dirty team, one not above cheap shots when it was apparent they couldn’t win cleanly.

Right or wrong, that was the story that hung over the game for fans in Tyrone for the next 20 years, and it only got worse when there were actual stakes involved.

PLUNDER

Pennsylvania has long been known for its passion for high school football. The 1980s classic All the Right Moves laid out clearly the emotions involved for the teams and their fanbases, particularly in Western PA.

That’s why it’s ironic it took the PIAA so long to get on board with statewide playoffs, which were not adopted until 1988. Before that, the grandest title in the commonwealth was a WPIAL championship, and before that (assuming you weren’t located in Pittsburgh), it was a Central Pennsylvania High School Football League title.

The league was divided into two sections – the Western Conference and the Eastern Conference – which used a formula to rank the teams and determine a champion from each division, and from 1922 through 1940, those teams played at the end of the season to determine what the league called a state champion.

Both Tyrone and Huntingdon played in the Western Conference, and by the 30s their yearly games went a long way in determining who would play for the title. Huntingdon never quite made it, but a couple of schools from District 6 did – Lock Haven in 1924 and Altoona in 1929 won it all, in fact.

Tyrone was often the bridesmaid, finishing just a game off the pace in the Western Conference.

Then 1940 came around, and the Eagles, under legendary coach Steve Jacobs, had a run that would be unmatched in the borough until the team in 1996 advanced to the PIAA championship. Tyrone won 12 straight games that season and played in the CPHSFL championship against Shenandoah, a game they tied 0-0 while playing in rain, snow, and drizzle that handicapped both teams’ offenses. That gave the Golden Eagles a shared state championship, but while the ultimate game of the season was somewhat anticlimactic, the game that got them there was anything but.

Tyrone’s fans, brimming with elation, stormed the field and proceeded to tear down the wooden goal posts. Huntingdon’s fans weren’t going to take the indignation sitting down, so they confronted the vandals.

It came in the last week of the season, on Thanksgiving, against Huntingdon at the Bearcats’ new field, which had not yet been christened War Veterans Field. Attendance was reported at 7,000, and the winner would claim the Western Conference championship.

Rainy weather made the playing surface treacherous, so Tyrone, known for slick play that was then known as “razzle-dazzle,” went to the ground, and outrushed Huntingdon 254-81. The Eagles won 13-0, setting off a celebration unlike anything the borough had ever seen, and like the game 16 years earlier at the Athletic Park, it probably set some narratives that burned and simmered for much longer.

Tyrone’s fans, brimming with elation, stormed the field and proceeded to tear down the wooden goal posts. Huntingdon’s fans weren’t going to take the indignation sitting down, so they confronted the vandals. According to a report in the Tyrone Daily Herald, fists were thrown and anatomies were bruised, but down came the goal post.

It was brought back to Tyrone and burned in the streets at the intersection of 10th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, as part of an enormous bonfire that nearly burned the street light overhead.

Ultimately, police and fire marshals had to subdue the blaze and the crowd. Arrests were made, fans were assaulted, and yadda-yadda-yadda, Tyrone eventually played for a state championship.(It would be the last state championship Pennsylvania would see for 48 years. The annual East-West game was put on hold in 1941 and never renewed.)

It was one more game that was anything but just one more game, and it began a period where not only the teams but the schools, as well, didn’t much care for each other. And it would get worse.

END IT

By the middle of the 40s, enough was enough for Huntingdon. In1946, the Bearcats were feeling their oats under Coach Jack Meloy, having won 32 of 34 games and two Western Conference championships.

That same season, the Bearcats spanked Tyrone 25-0, but at least one member of the media in Tyrone thought the game was one more sign of everything wrong with football in Huntingdon. The Bearcats, he said, were too rough, bordering on cheap and dirty, and that came from the top down.

Meloy, he said, was a J.G. Everhard guy, and not only was Everhard the superintendent of Huntingdon schools, he was also the coach of the team that way back in ’24 nearly killed Wib Ammerman. What could you expect, the writer wondered. Meloy, after all, had played for Everhard.

The writer opined that there was “evidence of the unsportsmanlike style of playing that is taught to the boys by the head of the school, J.G. Everhard, and their coach, Jack Meloy … The fault is not that of the youngsters for they play the way they are taught.”

That was about all Huntingdon could take. Like a bad relationship that had gone on too long almost out of habit, it was time for a clean breakup.

Although the game was the top draw on both teams’ schedules, their two-year contract, which had been renewed every year since the 1930s, was dropped, and it wouldn’t be renewed for another six seasons.

TITLES ON THE LINE

Ultimately, Tyrone and Huntingdon kissed and made up in 1952, and they’ve played every year since – the lone exception coming in 2021 when COVID restrictions forced a Bearcats forfeit. The result was the renewal of a rivalry series that simply had to be on both team’s schedule because for every time someone charged the game brought out the worst in both schools, there were 10 examples of it bringing out the best, and that was as true in the early years of the renewed series as it is today.

Nineteen Sixty-Four was a good example.

It was a season when Tyrone’s defense accomplished feats unmatched before or since, shutting out seven consecutive opponents during a 7-2-1 season. One of those shut outs came against Huntingdon in Week 4.

The game should have been unremarkable. The Eagles at 2-1 were beginning to settle into the championship form that had earned them a Central Counties title a year earlier. Huntingdon stumbled in to Gray Memorial Field at 1-2.

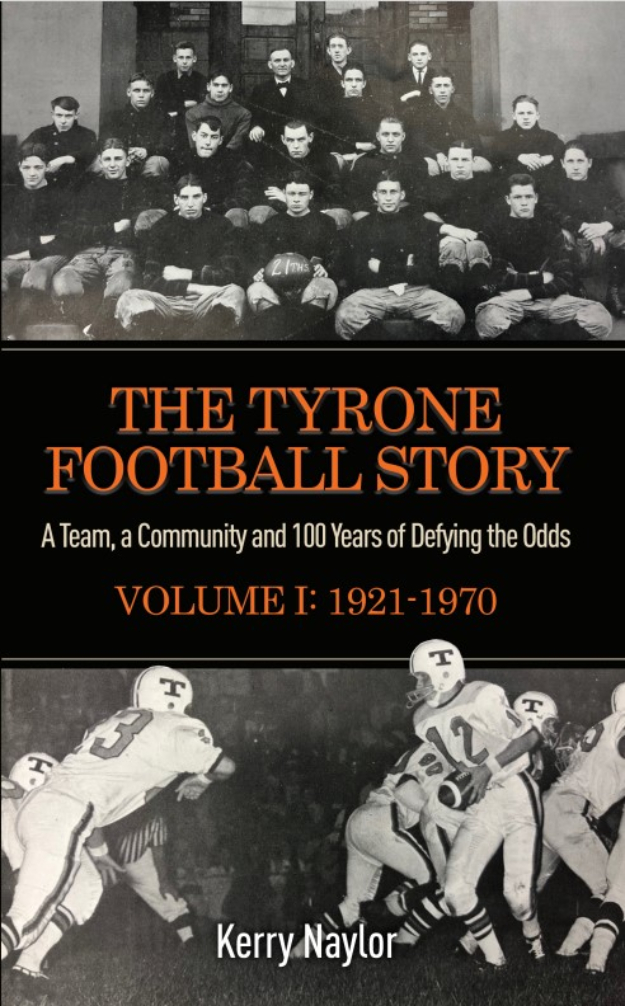

For more stories detailing the history of Tyrone football, go to this link to purchase Volumes 1 and 2 of The Tyrone Football Story: A Team, a Community, and 100 Years of Defying the Odds, first published in 2021.

But the teams were deadlocked 0-0 with time ticking away in the fourth quarter. Tyrone had dominated the ‘Cats, preventing as much as a first down until the third quarter, but had failed to convert on four scoring chances that penetrated the 30, one of which ended at the 5.

All Huntingdon had to do was milk the clock for a tie, which for Tyrone would have been as good as a loss in the Western Conference and Central Counties standings.

With 7 seconds left, Bearcat quarterback Ken Fagan took what should have been the final snap from his own 30, but rather than take a knee he pushed into the line, twisting as he did so. Tyrone lineman Gary DiDomenico saw an opening and snatched the ball from Fagan’s hands, and raced to the endzone for the game-winning score as time expired.

All Huntingdon had to do was milk the clock for a tie, which for Tyrone would have been as good as a loss in the Western Conference and Central Counties standings.

The games got even better with the added stakes of District playoffs and a solid conference that allowed for head-to-head competition between all of the members.

The Big 8 formed in 1973 (with only 6 member schools at the time), and by the 1980s it had become a pipeline to a District championship.

District 6 first began holding playoff tournaments for football in 1985, and by 1990, 5 of the first 6 champions in 3A came from the Big 8. The 3A finals featured two Big 8 schools in three of those years.

That meant the Tyrone-Huntingdon game, then generally played in Week 2, was a fast-track to the District title game, and that heated the series up more than assaults and vandalism ever did.

Both schools even got their first District crown at the expense of the other. In 1986, the teams faced off in the 3A championship at Hollidaysburg’s Golden Tiger Stadium, the crowning game in a 4-team tournament in which all of the participants had come from the Big 8.

Tyrone and Huntingdon had battled to a 7-7 draw earlier in the season, so a similar defensive struggle was expected for the title clash, and that’s exactly what fans got. Tyrone’s focus was limiting the ‘Cats’ top rusher, Sean Hoover, who had run for 2,700 yards in his career.

The Eagles accomplished that, holding Hoover to 80 yards on 27 carries. In bone-chilling temperatures, the plan was to force Huntingdon to throw, but the ‘Cats never deviated from their ground-and-pound identity with the exception of one play. Quarterback Tom Hudy passed once in the ’86 championship game, and the result was a 57-yard touchdown pass to Matt Elder in a 6-0 win.

It was devastating for the Eagles, who that season had won the Western Conference championship – the program’s first title since 1964. And it had to have been strange, indeed, when, 10 months later, they again faced Huntingdon in Week 2 of the 1987 regular season with two Huntingdon’s coaches leading the charge.

Chuck Hoover was a 1966 Tyrone grad who had played on the ’65 team that established defensive records, but by ’87 he had been teaching and coaching in Huntingdon for 12 years. He was hired early that year to replace Tom Miller, who had stepped down following the loss to Huntingdon in the 1986 championship game.

Hoover had never been a varsity head coach, but his staff was composed of men who had been entrenched in Tyrone football most of their adult lives, with the exception of one defensive guru he brought with him from Huntingdon – Jim Zauzig.

When Hoover and Zauzig opened their first season 0-2 – losing to not only arch-rival Bellwood-Antis but then Huntingdon – the men thought they would be chased from town with pitchforks. But the team quickly righted the ship and won 9 straight games.

The Golden Eagles in 1987 earned the moniker “Cardiac Kids” because in that 9-game streak they won three consecutive games with zero seconds left on the clock, including a Homecoming win over Philipsburg-Osceola in which a last second catch by Bill Kimberling off a tipped pass rocketed Tyrone to the top of the Big 8 standings.

Tyrone won the league, but waiting for them in the District 6 3A championship was Huntingdon.

It was a game played at War Vets Field, and it went back-and-forth, with the Eagles leading 13-7 at halftime before falling behind 19-13 in the fourth quarter on a Hudy touchdown pass to Cleveland Walker.

That set the stage for one more fantastic finish for the Eagles. On its final series, Tyrone drove as far as Huntingdon’s 10 before stalling on fourth down. But in a season spent taking lemons and making lemonade, there was no need to panic.

On the decisive play, the Eagles lined up backup quarterback John Supina at running back and pitched him the ball on a sweep to the left. Supina stopped, pivoted back to his right, and threw a strike to tight end Tom Getz, who had leaked into the right corner of the endzone.

The touchdown pass tied the game. Supina’s extra-point kick broke the tie, and Tyrone had claimed its first District title – with two Huntingdon guys leading the way.

Big 8 – Big Games

The series continued to produce more magical moments throughout the 90s. By 1994, Tyrone had lost to the ‘Cats six straight times and were trying to rebound from a low-point in the program where it had gone 4-35 from ’89 through ’92, losing 19 in a row at one point.

John Franco took over in 1994, and used a win over Huntingdon as the springboard to a .500 season. Tyrone trailed the ‘Cats 6-0 before winning 7-6 thanks to a hook-and-lateral play that ended with Marcus Owens scoring with just seconds remaining.

That began a string of four straight wins over Huntingdon for Tyrone, but in 1998 the ‘Cats spanked Tyrone 47-18 on their way to a 3A Western Finals appearance. The next season – one that ended with Tyrone winning a PIAA championship – Huntington actually went up 8-0 on Tyrone in Week 2 thanks to a 71-yard pass from Paul Kozak to JB Gibboney on the ‘Cats’ first play from scrimmage.

Tyrone rebounded to win 31-8 as Jesse Jones ran for 292 yards, but it was the only deficit the Eagles would face in the regular season.

Perhaps the best games of the series came just as the Big 8 was in its final stages, early in the 2000s. Both programs were playing at a high level, and because they were in different classifications by then, their Big 8 clashes meant everything.

The Eagles were a depleted team in 2001, but they managed to keep things close in a 15-6 loss. The Bearcats would go on to win the Big 8 championship that season, as they did in 2002, when they edged Tyrone 29-20 in their Week 2 contest. It was two straight losses for the Eagles, but they were young and had a lot of talent coming of age, much of it in its sophomore class.

Those players were juniors in 2003, when the two titans of the Big 8 would do battle on last time as members of the venerable league, which was closing its doors at the end of the season. Central had pulled out and was heading to the Laurel Highlands, and rather than search for one new member or compete as the Big 7, the league, in essence, decided to expand to the two-division Mountain Athletic Conference. So this was it.

And it was a legendary game. Tyrone led most of the way, but the Bearcats, led by versatile signal-caller Geoff Kozak, tied the game with under a minute to play on a quarterback sneak. This was nothing new for Kozak, who could run and pass with the best of them, but what made it incredible was the senior was nearly knocked from the game in the second quarter with he took a shot to the head that had coaches thinking he had gotten his bell rung. Coach Jim Zauzig reported afterwards that Kozak’s own teammates had a hard time understanding him in the huddle after the hit.

But the precautions taken for head injuries in 2025 didn’t exist in 2003, and Kozak played on. Not only did he tie the game and force overtime, but in the extra frame he booted a 34-yard field goal that decided the game.

Huntingdon had won the final three Big 8 championships, and when all was said and done Kozak had never lost a game to a Big 8 opponent in three seasons as a starter.

TIDE TURNS

Following the overtime win, Huntingdon had forged an enormous lead in its all-time series with Tyrone. The ‘Cats were up 42-25-4, and it seemed highly unlikely that the Eagles, even playing at the high level they were on in the 2000s (it was a team that won 35 consecutive regular season games from 2004-2008 and played for a state championship in 2011) could possibly get themselves back to .500.

But they did, going on a 20-year tear unlike anything seen in the series before or since, a run of success that included two more playoff wins for the Eagles.

Since that game in 2003, Tyrone has won 21 games against the ‘Cats, losing only 3, and after defeating Huntingdon 41-21 earlier this season, the Eagles had actually taken the lead in the series with 46 wins and 45 losses.

At one point from 2004 through 2016, Tyrone had claimed wins over Huntingdon in 15 straight games. In 2014, the teams squared off in the postseason for the first time in almost 30 years, and Tyrone won 42-15 in the 2A semifinals on its way to a District 6 championship.

The next year, after losing 42-27 in the regular season, the ‘Cats stayed in game in the District 6 quarterfinals and led 21-14 late in the third quarter following a 36-yard touchdown run by Jon Wagner. But Tyrone tied the game a minute-and-a-half into the fourth and drove the field late to set up a 24-yard field goal by Ethan Vipond with 29.7 seconds left to win it.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

All that history leads back to Friday, when the 7-3 Bearcats, the No. 2 seed in the 3A playoffs, host 6-4 Tyrone, which sneaked in at 3 with a win over Chestnut Ridge last week.

It’s a game that will take place on the same field where 85 years ago Tyrone fans were filled with such elation that stole a goal post.

No matter which team wins, a replay of that scene is highly unlikely, if for no other reason than the security presence at high school games has gotten a lot better over the last century.

But the game will add to a legacy forged more than 100 years ago, fueled initially by emotions that bordered on hate, and eventually built into a mutual respect for the accomplishments of the other.

One comment